ASU 2016-14 requires specific disclosures on the liquidity of your organization. It’s also an opportunity to show off your leadership’s strategic thinkin...

If you were playing a word game, throwing out the term “liquidity” in hopes that your teammate would respond with “strategy” is a longshot. Likewise, enthusiastically shouting out “FASB standard” might not automatically lead your partner to conjure up the word “inspiration.” But in the world of nonprofit accounting, there are some useful connections to be made between the new FASB standard on liquidity and an inspired financial strategy.

Liquidity may seem an unusual topic for nonprofits to consider at all. But discussions about liquidity — a measure of the availability and flexibility of an organization’s operating funds — are not optional for nonprofits anymore. At least not for those that are required to have an annual audit. The topic is important enough that the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) issued Accounting Standards Update (ASU) 2016-14, Presentation of Financial Statements of Not-for-Profit Entities, which includes requirements for specific disclosures on liquidity.

The new FASB standards can be the motivation for thinking through your financial plans and for showcasing creative ways your nonprofit manages its liquidity.

You can use this requirement as an opportunity to show off your leadership’s best strategic thinking. But to make a public display of your strategies means you’ll need to make sure your approaches to maintaining adequate financial resources for your nonprofit are up-to-date and well-designed.

How do you ensure your nonprofit has enough funds (and the right kinds) to meet its immediate operating needs? What policies, practices, and plans have you developed to ensure you have resources to move forward successfully? The new FASB standards can be the motivation for thinking through your financial plans and for showcasing creative ways your nonprofit manages liquidity.

Using FASB ASU 2016-14 to inspire better nonprofit financial strategies

Before we look at strategic questions involving liquidity, let’s get clear on how to satisfy FASB’s disclosure requirements regarding the availability and flexibility of your assets.

To demonstrate liquidity, you will need to identify financial assets that are available to meet cash needs for general expenditures within one year of the balance sheet date. At its simplest, describing availability means listing those assets (cash, accounts receivable, contributions receivable, short-term investments, etc.) that can be accessed within 12 months. Describing flexibility means listing those assets that have no donor restrictions, have not been designated by the board for any special purpose, and do not carry any other limitation on their use for general expenditure. Other limitations could be something like a minimum cash reserve required by a loan covenant or a compensating deposit required by a bank.

To help users of your financial statements understand the relative financial strength of your nonprofit, FASB asks you to share quantitative and qualitative information. What you report will require numbers (financial statements or tables) and narratives (note disclosures or explanations).

The beauty of a two-column, classified balance sheet

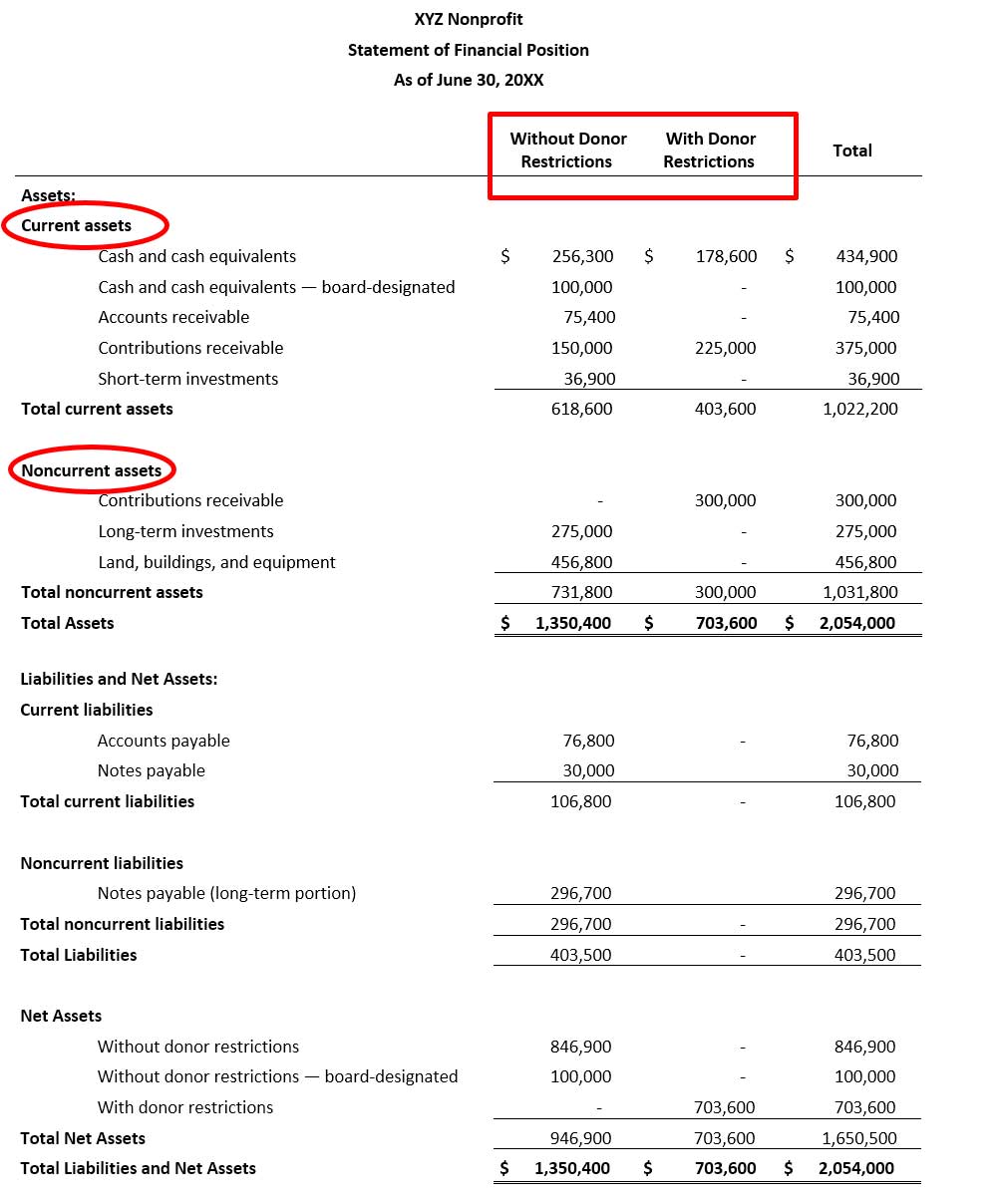

The requirement for displaying liquidity information can be partially satisfied by presenting a two-column, classified balance sheet or statement of financial position (see example below). This is a straightforward way to group assets and liabilities by their relative maturities. If an asset will be available or a liability will come due within 12 months of the balance sheet date, it is considered current. Otherwise, the asset or liability is considered noncurrent. To be considered available, an asset must generally be classified as current.

A statement of financial position can be made even more informative by using separate columns (not just line items) for the “without donor restrictions” and “with donor restrictions” categories — FASB’s new terms for what used to be called unrestricted, temporarily restricted, and permanently restricted. Showing which assets are available without donor restrictions helps statement users get a sense of what resources are the most flexible. To be considered flexible, an asset must generally be classified as without donor restriction.

Satisfying the standards may tell only part of your story

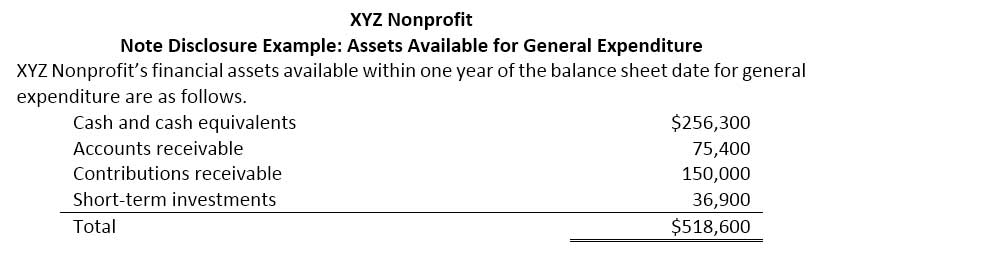

Although the classified statement of financial position provides excellent information to an experienced user, an audit note disclosure could also provide the necessary quantitative information with a table as simple as this:

While this table is more concise than the full statement of financial position, it lists only those portions of each line item that are available and flexible within the narrowest FASB definition. This list only displays current assets without donor restrictions. Most nonprofits are likely to use other assets throughout the coming year to accomplish their program work, even though they do not technically meet the definition of available and flexible. That’s why you are better off considering your liquidity strategies before writing the notes that provide the qualitative information required by the standards. With thoughtful planning, you will have a better story to tell about the full range of resources you have available for your work, how flexible those funds are, and how you intend to manage them.

Disclose how your nonprofit really works

Because of the way nonprofit business models work, many assets that do not qualify as available and flexible in FASB’s definition will nevertheless be used to support your organization’s work in the coming year. It is important not to confuse “assets available for general expenditure” with the total assets available to meet program and operating expenses.

We recommend expanding your narrative disclosure beyond the minimum FASB requirements to reveal the strategies and goals that guide how your organization manages its liquidity. This might include:

- Discussing reserve policies

- Outlining how you handle multiple receivables cycles (contributions or earned revenue)

- Describing when and how you use lines of credit

- Defining your process for estimating when and how much money will be released from restriction

All are appropriate topics for the qualitative portion of your disclosures. All demand attention and deliberate consideration by your board and leadership.

To determine reserves, consider income and expense cycles

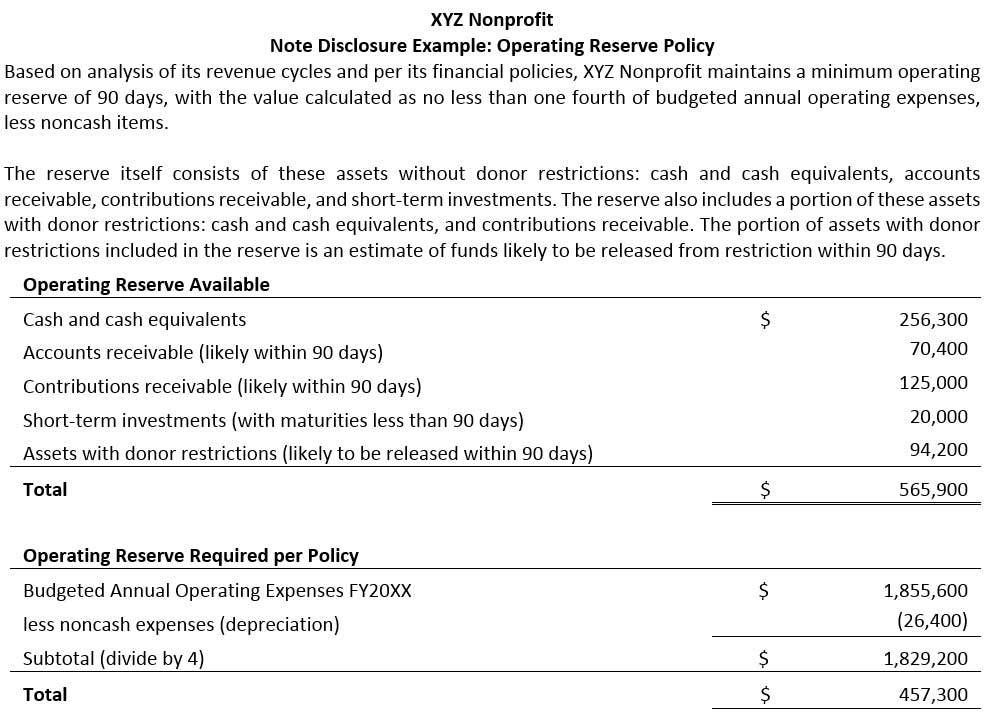

Having a reserve policy in place and communicating it in an audit note disclosure is a great sign that your organization is conscientious about its financial health. Developing a reserve policy is highly recommended for all nonprofits, even those that are new and struggling with the financial uncertainty of the early startup phase.

There is no standard answer as to how much money your nonprofit should hold as a reserve against unexpected operating shortfalls. You may have heard 90 days or six months of cash-on-hand thrown around so often that those amounts seem like the right answers. But each nonprofit has its own receivables cycle (contributions and/or earned revenue) and expenditures cycle (spending patterns) that determine how much it needs to guard against potential shortfalls. FASB’s definition of availability is tied to the conventional 12-month accounting cycle, but most nonprofits have operating and revenue cycles that do not conveniently match the 12-month model.

One way to determine what your operating reserve should be is to consider your main sources of income. For example, if your organization receives nearly all of its income from individual contributors who give 90 percent of their gifts in November and December each year, then your organization may need to aim for a reserve equal to a year’s worth of those contributions. If, for some reason, your annual giving campaign was interrupted or diminished, your organization would need to have nearly a full year of reserves to survive the 12 months between one campaign and the next.

Similarly, if your organization receives the majority of its funding from contracts with government agencies that pay on a typical 90- to 120-day delay, then you might choose to have a reserve equal to 120 days of operating expenses. If the governmental unit that funds you is experiencing political or fiscal uncertainty, you may find it prudent to increase your reserves. Whatever level you choose, it should be set to match the natural cycles of your business model and take into account any economic, political, and business risks that are in play.

These examples illustrate that each nonprofit should consider its own particular receivables and expense cycles. More complex organizations may need to consider multiple receivables cycles from different sources, adapt to highly-variable salary and wage expenses tied to seasonal hiring practices, or make plans for other types of reserves targeted to specific purposes.

Other reserve policies to consider

Operating reserves are the most common type of reserves, but they’re not the only ones. Your organization may wish to establish policies about:

- Capital reserves for buildings or equipment

- Program expansion reserves to fund the addition of new staff or services

- Opportunity reserves so you can respond quickly to new, unexpected mission initiatives and projects

Whatever reserve policies you create, including them in the liquidity disclosure shows your organization is taking a sophisticated approach to ensuring it has funds to cover necessary expenses.

Maybe not flexible, but certainly spendable

For the most part, FASB’s basic liquidity measure includes only those assets that are both current and without donor restriction. These are certainly the most flexible assets a nonprofit could have. They are true operating reserves and could be used for any purpose.

However, without further explanation in the note disclosures on liquidity, it would be easy to misinterpret this measure to be the total funds available for operations. Taken out of context, it could give the mistaken impression that the nonprofit has limited funds for the coming year’s program and operating needs.

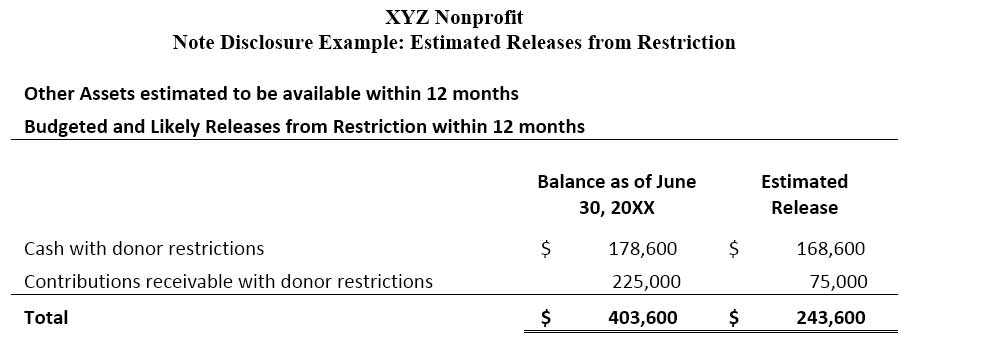

To counter this misconception, nonprofits may choose to expand their note disclosure to include information on other sources of funds and other assets that will support day-to-day programs and operations over the coming year. Contributions with donor restrictions are often a large part of nonprofit revenue streams. These funds may not be considered flexible and could not be included in the table above that lists only assets “available for general expenditure.” But they are spendable.

To give a more complete picture of what funds your organization will have available to accomplish its program and mission goals, your disclosure could provide supplemental information, including an estimate of how much revenue is expected to be released from restriction in the coming year.

Similarly, you may also use your note disclosure to offer insights into your budgeting process, share how you monitor the release of donor restrictions, and display lines of credit or other off-balance-sheet resources you use to manage liquidity. Whatever information you choose to share, the qualitative portion should give financial statement users insight into how your organization ensures it has ample financial resources.

Strategies for liquidity: showcasing your financial sophistication

Though you still may not associate liquidity with strategy or FASB with inspiration, the new FASB standards really do offer incentive to tell a more complete and compelling story about how your organization manages its funds. A well-thought-out and well-crafted narrative about how your nonprofit tends to its assets is essential (and now required) to give financial statement readers a full picture of your organization’s fiscal well-being. Displaying the hard work of your financially-savvy and engaged management team can make a good impression with potential supporters. Making the process your organization uses to review, monitor, and address liquidity more transparent can help build well-deserved trust and confidence in your organization.

How we can help

CLA’s extensive experience with nonprofit organizations allows our professionals to go beyond accounting standards and regulations. Our goal is to understand your organization’s goals, and consult with you on financial management, grant compliance, information security, tax compliance, and other strategic issues that enhance your ability to fulfill your mission.